A Fading Art: Neon Signs

Our friend, Kristen Peterson, called me a few weeks ago regarding an article she was writing for the Las Vegas Weekly on the dying art of neon sign designing.

I was very happy to talk to her about the subject and the neon I remembered from my childhood days growing up in the City of Neon.

During the 1960s the Golden Nugget’s neon sign floated at night. Its supports were unlit and undetectable, leaving the neon framed by the dark.

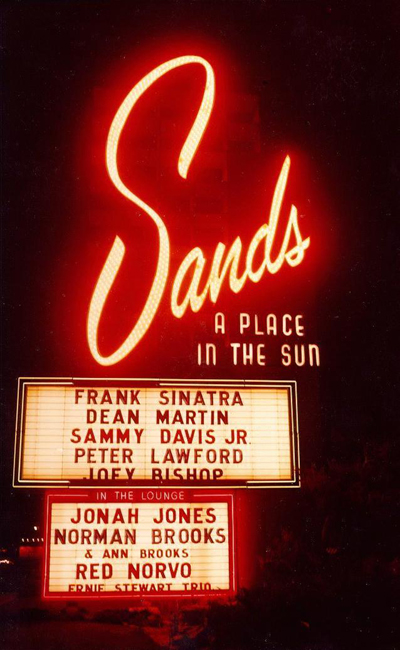

Lynn Zook was in awe of the way it seemed to hang in space. But that’s how it was when neon was king—glowing, elegant scripts, rendered objects and themed characters celebrated, with little distraction, the designs of Buzz Leming, Betty Willis, Herman Boernge and others.

Neon benders worked long hours, sometimes around the clock. They were artisans, journeymen who started out as apprentices and followed generations of benders in one family. Their work was noticed around the world. Photographs and movies captured the neon artistry.

But neon in Las Vegas has come to a near standstill. It’s a dying art, many of its relics laid to rest in the Neon Museum’s Boneyard while high-tech LED screens bombard tourists meandering the circuitry of an all-encompassing computerized blitz.

“Back in the day, designers created to catch your eye,” says Zook, a historian for Friends of Classic Las Vegas who grew up here in the ’60s. “It’s all very overwhelming now because your eye doesn’t know where to look.

“It was beautiful to drive down the street back then. There was motion because the signs moved, but it didn’t feel like your head was going to explode. LED is creative in its own way, but it’s not as humanizing.”

At Casino Lighting & Sign crews build a new entrance to Planet Hollywood on a workbench that measures 20 by 40 feet. Signs here are large construction projects: the CityCenter and Bellagio signs off the freeway, the Strip’s Harley Davidson Cafe motorcycle sign, M&M World’s exterior and the façade that ribbons across Planet Hollywood. Some projects span 200 feet.

But behind an unmarked door in a much smaller workspace, neon benders are fusing glass tubes, melting, bending, shaping and sealing.

One of them is Bong Gonzalez, 42, who has been doing this since he was 17. He was trained by his father and grandfather, who learned how to bend neon in the Philippines. “My grandpa always said, the more burns you got, the better you’re getting. The burns mean that you’re learning.”

Gonzalez and Al Ybabao are all that’s left in the neon department at Casino Lighting & Sign. Today there just isn’t demand. Nor are there calls from eager young apprentices. No new meat. Sign benders are becoming an endangered species.

“Back in ’98 we had five guys in here,” Gonzalez says. “It was hectic in those days. We were working 16-hour days and you couldn’t rush it.”

The other major neon companies have scaled back, too. Young Electric Sign Company (YESCO), which has been in Las Vegas since the 1930s and helped launch the Golden Age of Neon, has three sign benders left. Nevada Sign and Federal Heath Sign Co. each have one.

“It’s a very labor-intensive process,” says Joe DeJesus, vice president of Casino Lighting & Sign. “A good glass blower takes many years to learn his trade. It’s sad to me that we need fewer of them as time goes by.

“A lot of signs in Las Vegas have gone from being the big spectacular stuff to the more architectural,” he says. “The advent of LED projects definitely affects the volume of neon we do now.”

DeJesus knows the history. Formerly with Ad Art, he got his start in the industry sweeping floors in a friend’s dad’s sign shop while in high school.

“I loved neon. I hoped it would never get replaced. It was so gradual that it didn’t really dawn on some of us at first. They were dear old friends. Stardust was one of the iconic signs of Las Vegas. It was a tragedy to see it go.”

The Stardust sign, rescued when the building was imploded in 2007, now sits over at the Neon Museum on Las Vegas Boulevard North. It’s one of 150 signs there (450 unique objects), most of which are neon. More will surely arrive as signs dim, buildings go and businesses completely eschew the neon advertising that was once a commercial staple.

For some, moving away from neon is easy. “As much as we love neon, we hate it,” says John Williams, division manager at YESCO. “It’s difficult to deal with. It’s all handmade and it’s dangerous.”

Safety precautions, difficult installation and wiring codes make it worse.

Williams says that YESCO has hundreds of miles of neon in Las Vegas, but like Bong and Al, the neon benders at that company now mostly do repairs and minimal creative projects. “At one time we had eight working full-time and a lot working overtime. Now we have three.”

YESCO anticipated this evolution for a number of years as LED became more economically feasible and energy efficient. The transition, Williams says, was an easy one for artistic designers: “They like it because it gives them more flexibility. With LED we’ve got millions of colors. With neon, we have less than 100.”

Williams says neon still has its place, particularly when dealing with the complexity of linear light, dramatic curves and shapes and the desired smooth consistence of illumination.

Neon was discovered as an element in 1898 by British scientists William Ramsay and Morris Travers. The first neon bulb was created by Georges Claude in 1902 when he charged a sealed tube of glass containing the inert gas with an electrical current. By 1915, Claude had patented his product, and neon became a primary advertising tool, arriving in the U.S. in 1923 when a Los Angeles auto dealership installed two works.

Historians attribute Las Vegas’ first neon sign to Downtown’s Boulder Club, though nobody seems entirely certain. They agree, however, that the 1940s were Las Vegas neon’s golden years, and that the art form had started losing ground to newer technology as early as the 1970s.

LED has been bundled in with the Green Movement, and it’s everywhere you look now. It requires less power than neon; it’s less fragile; and it doesn’t have the mercury required to brighten argon (the blue element in signs), which makes neon dangerous to handle. Even the Neon Museum’s Boneyard Park includes LED lights made to replicate neon.

But Eric Elizondo doesn’t think neon’s life is over. The YESCO tube bender believes his medium will make a comeback, and he’s watching for promising signals.

“I have faith in it,” he says. “People like the look of neon.”

Elizondo has been working in neon for 35 years, starting in the summers during high school and moving full-time after graduation. His dad and grandfather were sign benders. “Most of us grew up with moms and dads doing it, then you end up doing it.”

Elizondo’s dad, Sergio, made the neon for the original Welcome to Fabulous Las Vegas sign while at Western Sign, and Elizondo made the neon for the Boulder Highway sign created in the same style. Elizondo’s son would have been a fourth-generation sign bender, but he was laid off.

Maybe when the Neon Museum opens next year, interest will resurface. The Museum already receives 12,000 visitors annually through prescheduled tours, and its Fremont Street gallery already includes nine restored, iconic neon signs. Three classic signs have been restored for the scenic byway project on Las Vegas Boulevard: Binion’s Horseshoe, the Silver Slipper and the Bow and Arrow sign. Danielle Kelly, the museum’s operations manager (and the Weekly’s art critic), says three more signs will be restored and added to the Boulevard this fall. The museum is also reigniting its Living Museum, which includes signs that have been promised to the museum should anything happen to their buildings or businesses. When the museum opens, a brochure will be offered to visitors interested in viewing them.

The museum prefers that signs remain in situ, and Kelly heralded the efforts for the iconic Davy’s Locker sign on Desert Inn and Maryland Parkway. If businesses knew the love that people have for neon, they might not be so quick to abandon it, she says.

“People do miss neon. It’s who we are. Las Vegas grew up on it on TV, in movies and in print media. People grew up with these signs so they have personal, sincere memories, even if they’ve never been to Las Vegas.”

Outgoing Mayor Oscar Goodman equates neon’s importance to Las Vegas with jazz’s to New Orleans. The Boneyard, started by YESCO as a storage lot for its old signs, is at least a place for Las Vegas’ neon work to live in perpetuity.

Of course, neon isn’t dead yet. Casinos still call for small neon projects and Downtown businesses have brought in new neon works. City code requires neon or animated signs in the Fremont East Entertainment District and the designated scenic byway that is Las Vegas Boulevard. Jennifer Cornthwaite, who created and operates Emergency Arts, a Downtown multi-use creative space in an old medical building that was once a JCPenney, opted for a neon sign because, she says, it stays true to Downtown and the preservation of the neighborhood’s history. The animated red cross on the building, accompanied by backlit letters, was made and installed by Casino Lighting & Sign.

Zook still remembers what Las Vegas looked like when it was full of neon. “Everyone remembers the big casino signs, the big Strip signs, but it was in the neighborhoods. It was everywhere.”

Reader Comments (2)