Neon, Las Vegas and Designer Hermon Boernge

Post-War America was a time of unbridled optimism and exuberance. After years of fighting in Europe and the Pacific Theaters, the men who returned home wanted to settle down, raise their families and see America. Their families, no longer having to deal with ration stamps, victory gardens and the sacrifices made on the home front, wanted to return to their normal lives.

America had emerged from the war as the pre-eminent power. As the War years were put behind us, there emerged from the ashes of self-sacrifice and duty, a sense of anything was possible. This was reflected in many walks of life, perhaps nowhere as much in the architecture and signage of the era.

America was leaving behind its rural roots and becoming an automobile society. Route 66, the Mother Road, had led the pilgrims from Chicago to the shiny shores of California. During the Depression, it had been the road of choice for those headed west trying to escape the ravages of the Dust Bowl.

Now, it (and Dinah Shore and Chevy) were beckoning Americans to see the "USA in their Chevrolets" and Americans responded. From the California Crazy movement of buildings shaped like objects to the shores of Wildwoods, New Jersey and its Doo-Wop motels, America was on the move.

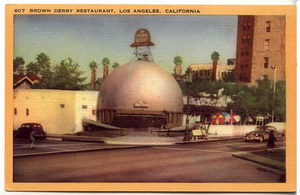

The Brown Derby in Los Angeles, CA

The Star Lux Hotel in Wildwoods, New Jersey

Neon signage fit into this perfectly. Fanciful signs beckoned the weary travelers to stop in, gas up, eat, sleep or grab one for the road.

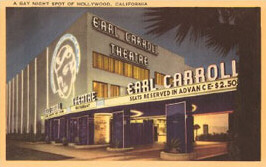

Neon had been invented in France in 1910 by Georges Claude. The first known USA commercial use of it as signage was in 1923 at Earle C. Anthony's Packard dealership in Downtown Los Angeles. Soon Los Angeles was aglow with neon rooftop signs, movie palace marquees and blazing, whimsical signage.

Neon designer, Betty Willis, who was born in Las Vegas in 1922, would travel with her family to Los Angeles a few times a year. One of her earliest memories of those trips was the blazing, movie marquees and the neon signage. She thought it would be fun to one day design in neon.

Las Vegas would become one of the most photographed cities in the world mainly because of its neon signage. From Downtown's Glitter Gulch to the Las Vegas Strip, neon was not only accepted but expected in Las Vegas. The Young Electric Sign Company, better known as YESCO, had arrived in town in the mid-1930s. Their first sign was the Boulder Club on Fremont Street. That sign put YESCO, on the map in Las Vegas and the company never looked back.

In Las Vegas, it was a convergence of architects such as Wayne McAllister and Richard Stadelman, working with visionary gaming pioneers such as Tommy Hull, Wilbur Clark, Jack Entratter and Jakie Friedman, Moe Dalitz as well as pioneering sign designers such as YESCO's Hermon Boernge, Kermit Wayne, Ben Mitchum and Jack Larsen that altered the skyline of Las Vegas forever.

Sweeping porte-cocheres, pulsating signs that shot neon into the heaven and could be seen for miles down the dusty highway, mid-century architecture that beckoned the weary traveler to pull in off the highway and stay not only the night but the weekend.

It was a mythic time in Las Vegas. What had started with Tommy Hull's El Rancho Vegas and Griffith and Moore's The Last Frontier was taking off. If nothing else, the Flamingo had heralded the start of the Las Vegas Strip resort hotels that were real carpet joints. Gone was the flair of the town's western roots. In its place were large (at least for their day), air conditioned, swanky hotels and casinos that emphasized their architecture and signage.

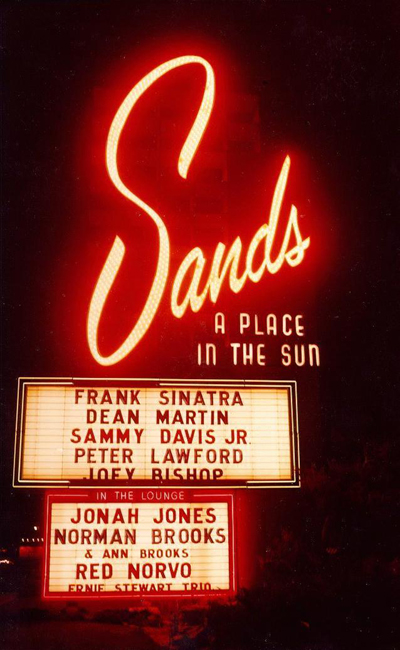

The original Sands Hotel. The first thing you saw, as you ambled down the two lane road that was Highway 91, was that giant Sands sign. At night, the letters spelling out Sands could be seen for miles. The hotel itself was not set back very far from the highway. The short drive up to the hotel led to an elegant porte cochere where air conditioned splendor beckoned from just the other side of wall to ceiling plate glass windows. Designed by Wayne McAllister, the Sands evoked a sense of fun and swank. It also helped that Jack Entratter, the Entertainment Director, booked some of the finest entertainers of the day into the Copa Room.

But, aside from the Copa Room, what we tend to remember most is that sign.

The sign would start lighting up from the top of the S and follow through until the whole sign glowed bright red in the night sky. There were no high rise buildings on the Strip in that era so the Sands sign could be seen for miles down the highway. It was a beacon in the night and as travelers got closer, they could marvel over the entertainers whose names were on the marquees.

It had started with the neon windmill at the El Rancho Vegas but the Sands sign, designed by architect Wayne McAllister and fabricated by YESCO, brought a new era of signage to Las Vegas where the sign and the building would meld together into one.

Hermon Boernge, along with Kermit Wayne, Ben Mitchum and Jack Larsen, was one of the pioneering sign designers in Las Vegas. His signs included the original Flamingo sign with its signature flamingo sketched at the top. Travelers who had left Beverly Hills far behind, writes Alan Hess, in "Viva Las Vegas: Architecture after Dark", "rediscovered that sophistication in Las Vegas." This was, in no small part, due to designers like Hermon Boernge.

The Original Flamingo front with the pylon sign by Hermon Boernge

Boernge also designed the Desert Inn, the Golden Nugget (with Kermit Wayne), Vegas Vic (some design work), a variety of small motel signage in Boulder City and some of the motels such as Gaslight, that used to dot the highway between the Strip and Downtown.

Unlike the frontier themed gambling halls on Fremont Street, the Golden Nugget sought to evoke the California Gold Rush era of opulent San Francisco. With its filigree Victorian rooftop sign that seemed to float in the night time sky 100 feet above the casino, Boernge captured the flavor and that era using a mixture of neon and incandescent light. The sign became a landmark on Fremont Street. Over the years, the Golden Nugget became one of the most photographed signs in the world.

The Golden Nugget sign seemingly suspended above Fremont Street. Sign by Hermon Boernge and Kermit Wayne.

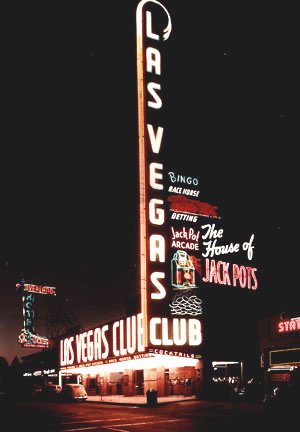

In 1951, Boernge designed the 120-foot Moderne sign for the Las Vegas Club. With neon that started lighting from the top, it flowed down the tower. At the base was a Slot Machine spilling out neon coins.

The Las Vegas Club sign, designed by Hermon Boernge

Perhaps the most memorable and most cherished sign that Boernge designed, in collaboration with Kermit Wayne, was the incredible Mint Hotel and Casino sign. This sign set a new standard for neon signage in Las Vegas. Working with architects, Walter Zick and Harris Sharp, Boernge and Wayne fleshed out the design. It was the perfect conflux of architecture, signage and artistry.

Zick and Sharp were post-war graduates of USC's School of Architecture. As Alan Hess points out, they were familiar with the abstractions of modern architecture. But working with Boernge and Wayne, they created something much more potent and organic that far surpassed the rudimentary (by comparison) look of the Boulder Club or the Las Vegas Club.

The Mint signage heralded the arrival of the jet and space age in America. The signage had incredible depth. It united the traditional vertical pylon with the horizontal marquee. The sign started its lighting run at the bottom of the horizontal marquee and ran in a swoop up over the entrance and then up the pylon finishing off by lighting the starburst at the top.

During the day it was a marvel to behold but from twilight on, it was spectacular. Fremont Street has never had a sign to rival it. When Benny Binion bought the Mint in the early 1990s, the Mint sign was destroyed as the Horseshoe facade replaced it. To this day, when people talk about lost hotels and lost signage, the Mint is the most talked about. People have a sadness in their voice when they talk about it.

It recently made an appearance, thanks to CGI, on an episode of "CSI". Despite having a different name on the hotel, the bright pink swoop and starburst at the top, brought back for just a few seconds, the Mint in all its neon glory.

Hermon Boernge, Kermit Wayne, Jack Larsen and Ben Mitchum were all sign designers working with neon and incandescent lights during the early days of Classic Las Vegas. For the most part, their stories and their signs are lost to history. The often worked with constraints from the client and/or the salesmen, and Alan Hess reminds us, often the salesmen held them in contempt. Many people back in the day did not consider the signs or the work that went into them to be art. Yet, despite all the constraints, they crafted some of the most iconic neon images of the 20th Century.

They came from varied backgrounds. Jack Larsen worked for Walt Disney Studios in the 1930s. Kermit Wayne painted theatrical posters and lobby cards for a theater chain in Chicago. After the war, he went to work for MGM Studios in Culver City as a scenic artist. Working with a team of other artists, he created the giant backdrop murals of cityscapes and skies for soundstages. It taught Wayne how important scale was in design. It was a lesson that would serve him well, as we shall see, when he left MGM and moved to Las Vegas to work for YESCO.

Hermon Boernge worked for YESCO into the 1960s. He died in the late 1960s

Their legacy, however, was passed on to the generation of sign designers, such as Betty Willis, Brian "Buzz" Leming, Raul Rodriguez and others who picked up the neon torch and carried Las Vegas signage into the 1960s and 1970s.

We will be exploring more of their stories and their legacies here so stay tuned, stay subscribed and feel free to post your comments or ask questions.

Visit our Classic Las Vegas Neon Photo Gallery here.

Special thanks to RoadsidePictures, Eric Lynxwiler, Nevada State Museum, UNLV's Special Collections, Alan Hess, Chris Nichols and the Las Vegas Review Journal for letting us use their photos.